Table of Contents

ToggleThere’s been a lot of discussion about the actual impact of a healthy lifestyle on our health.

That’s why I decided to perform a case study about the impact of a healthy lifestyle on our health. Healthy lifestyle examples include getting more sleep, exercising, a healthy diet, not smoking, and so on.

To reach an optimal conclusion, I decided to perform a case study by searching various scientific databases such as PubMed, Directory of Open Access Journals, and Google Scholar.

This way, I made sure to find and research the best available scientific articles regarding healthy lifestyle aspects and their impact on our emotional and physical well-being.

Healthy lifestyle case study

Yanping Li et al. (2019) concluded in the following study, that people living their lives following five low-risk lifestyle factors could potentially substantially reduce premature mortality and prolong life expectancy in US adults. [1]Li, Yanping et al. “Impact of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on Life Expectancies in the US Population.” Circulation vol. 138,4 (2018): 345-355. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032047

These five low-risk lifestyle factors are:

- Never smoking

- Body mass index (BMI) 18.5–24.9 kg/m2

- 30+ minutes/day of moderate to vigorous physical activity

- Moderate alcohol intake

- Healthy diet

In the following lifestyle study performed by Dariush D. FARHUD (2015) he concludes that according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 60% of related factors to individual health and quality of life are correlated to lifestyle. [2]Farhud, Dariush D. “Impact of Lifestyle on Health.” Iranian Journal of Public Health vol. 44,11 (2015): 1442-4.

According to his study, the reformation of unhealthy lifestyles is a preventing factor for decreasing the rate of genetic diseases.

Furthermore, he argues that in some countries, the overuse of drugs instead of other interventions can harm the immune system.

According to the study, 9 different domains for a healthy lifestyle should be differentiated.

- Diet and Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Exercise

- Sleep

- Sexual behavior

- Substance abuse

- Medication abuse

- Application of modern technologies

- Recreation

- Study

Grimaldo performed a lifestyle study in 2010 and concluded that a healthy lifestyle comprises three areas of habits and behaviors. Namely, sports, repose/sleep habits, and food consumption. [3]Grimaldo Muchotrigo, M. Calidad De Vida Y Estilo De Vida Saludable En Un Grupo De Estudiantes De Posgrado De La Ciudad De Lima. Pensamiento Psicológico, Vol. 8, n.º 15, Dec. 2010, … Continue reading

The findings of the study show that there is a close relationship between sleep and quality of life.No correlation was found between the quality of life and sporting activity.A positive correlation was found between health and eating habits in the youngest age group, although further research is necessary with other sample groups.

Nanbo Zhu et al. published the following article that concluded that adherence to a healthy lifestyle was associated with substantially lower risks of all-cause, cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer mortality in Chinese adults. The promotion of a healthy lifestyle may considerably reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases in China. [4]Zhu, N., Yu, C., Guo, Y. et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Chinese adults: a 10-year prospective study of 0.5 million people. Int J Behav Nutr Phys … Continue reading

They established the following 5 healthy lifestyle factors:

- Never smoking or smoking cessation not due to illness

- Non-daily drinking or moderate alcohol drinking

- Median or higher level of physical activity

- A diet rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, and fish, and limited in red meat

- A body mass index of 18.5 to 27.9 kg/m2 and a waist circumference < 90 cm (men)/85 cm (women)

Bergens et al. (2020) have suggested that healthy dietary patterns characterized by high intakes of fruit and vegetables may infer protective health effects through various mechanisms including increased anti-oxidative defenses and reduced circulating levels of several inflammatory biomarkers. [5]Bergens, Oscar MSc; Veen, Jort MSc; Montiel-Rojas, Diego MSc; Edholm, Peter MSc; Kadi, Fawzi PhD; Nilsson, Andreas PhD∗ Impact of healthy diet and physical activity on metabolic health in men and … Continue reading

It is currently proposed that an interaction between a systemic pro-inflammatory environment and the metabolic machinery causes a state of metabolic inflammation (metaflammation), which promotes chronic disease progression.

He concludes that given the global epidemic of metabolic diseases, healthy lifestyles in late adulthood hold important potential to counteract this trend.

Laura Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva et al., have established clear links in the following study between psychological well-being (PWB) and lifestyle factors such as physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and dietary patterns in people above the age of 44. [6]Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva L, Luksiene D, Virviciute D, et al Link between healthy lifestyle and psychological well-being in Lithuanian adults aged 45–72: a cross-sectional study BMJ Open … Continue reading

The following statement is the researchers’ conclusion.

Healthy lifestyle education efforts should focus on increasing physical activity, controlling smoking and improving diversity in healthy food consumption including the consumption of fresh vegetables and fruits, particularly among older adults with lower psychological well-being (PWB).

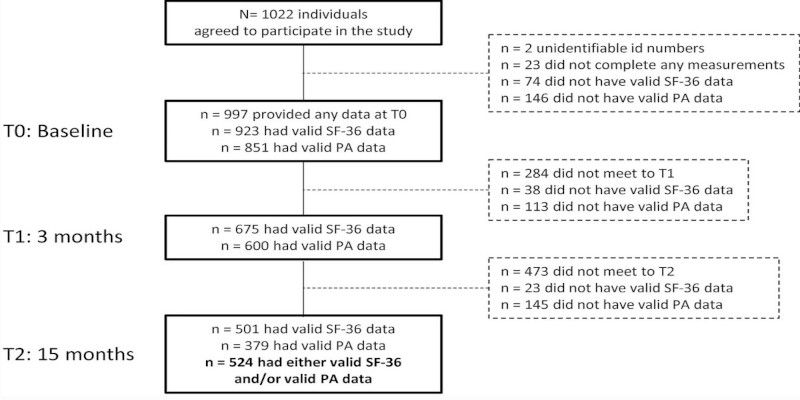

Blom, E.E. et al. (2020) published a paper observing the long-term impact of primary care behavior change programs on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and physical activity (PA). [7]Blom, E.E., Aadland, E., Skrove, G.K. et al. Health-related quality of life and physical activity level after a behavior change program at Norwegian healthy life centers: a 15-month follow-up. Qual … Continue reading

The following statement is their conclusion:

Twelve months after completing a 3-month healthy life center (HLC) intervention we found improved health-related quality of life (HRQoL), but not physical activity (PA) level. Still, there were positive associations between PA and HRQoL over this period, indicating that participants increasing their physical activity were more likely to improve their health-related quality of life.

Iffath U. B. Syed published an article after investigating a single case study in Canada, an under-researched area consisting of the health practices of healthcare workers from high-stress, high-turnover environments. In particular, it identifies LTC worker’s mechanisms for maintaining physical, emotional, and social well-being. [8]Syed, I.U.B. Diet, physical activity, and emotional health: what works, what doesn’t, and why we need integrated solutions for total worker health. BMC Public Health 20, 152 (2020). … Continue reading

The following statement is the summarization of his research.

while particular mechanisms were prevalent, such as through diet and exercise, they were often conducted in group settings or tied to emotional health, suggesting important social and mental health contexts to these behaviors.

Furthermore, there were financial barriers that prevented workers from participating in these activities and achieving health benefits, suggesting that structurally, social determinants of health (SDoH), such as income and income distribution, are contextually important.

Janas Harrington et al. published the following article in the European Journal of Public Health regarding the combination of four protective lifestyle behaviors. [9]Janas Harrington, Ivan J. Perry, Jennifer Lutomski, Anthony P. Fitzgerald, Frances Shiely, Hannah McGee, Margaret M. Barry, Eric Van Lente, Karen Morgan, Emer Shelley, Living longer and feeling … Continue reading

These protective behaviors are:

- Being physically active

- Non-smoker

- Moderate alcohol consumer

- Having adequate fruit and vegetable intake

These four protective lifestyle behaviors have been estimated to increase life expectancy by 14 years. However, the effect of adopting these lifestyle behaviors on general health, obesity, and mental health is less defined. This article examined the combined effect of these behaviors on self-rated health, overweight/obesity, and depression.

They concluded the following:

Adoption of core protective lifestyle factors known to increase life expectancy is associated with positive self-rated health, healthier weight and better mental health. These lifestyles have the potential to add quality and quantity to life.

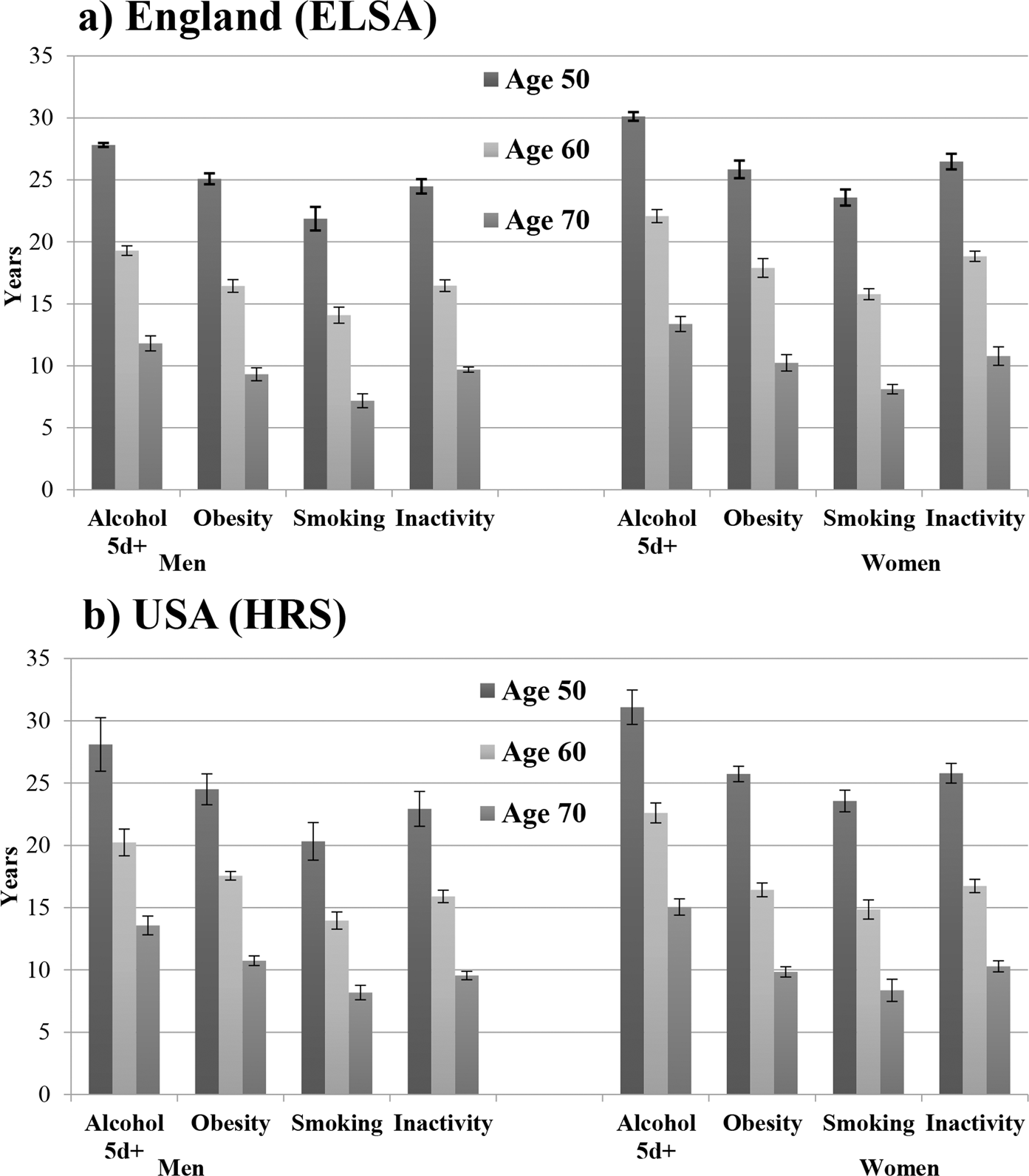

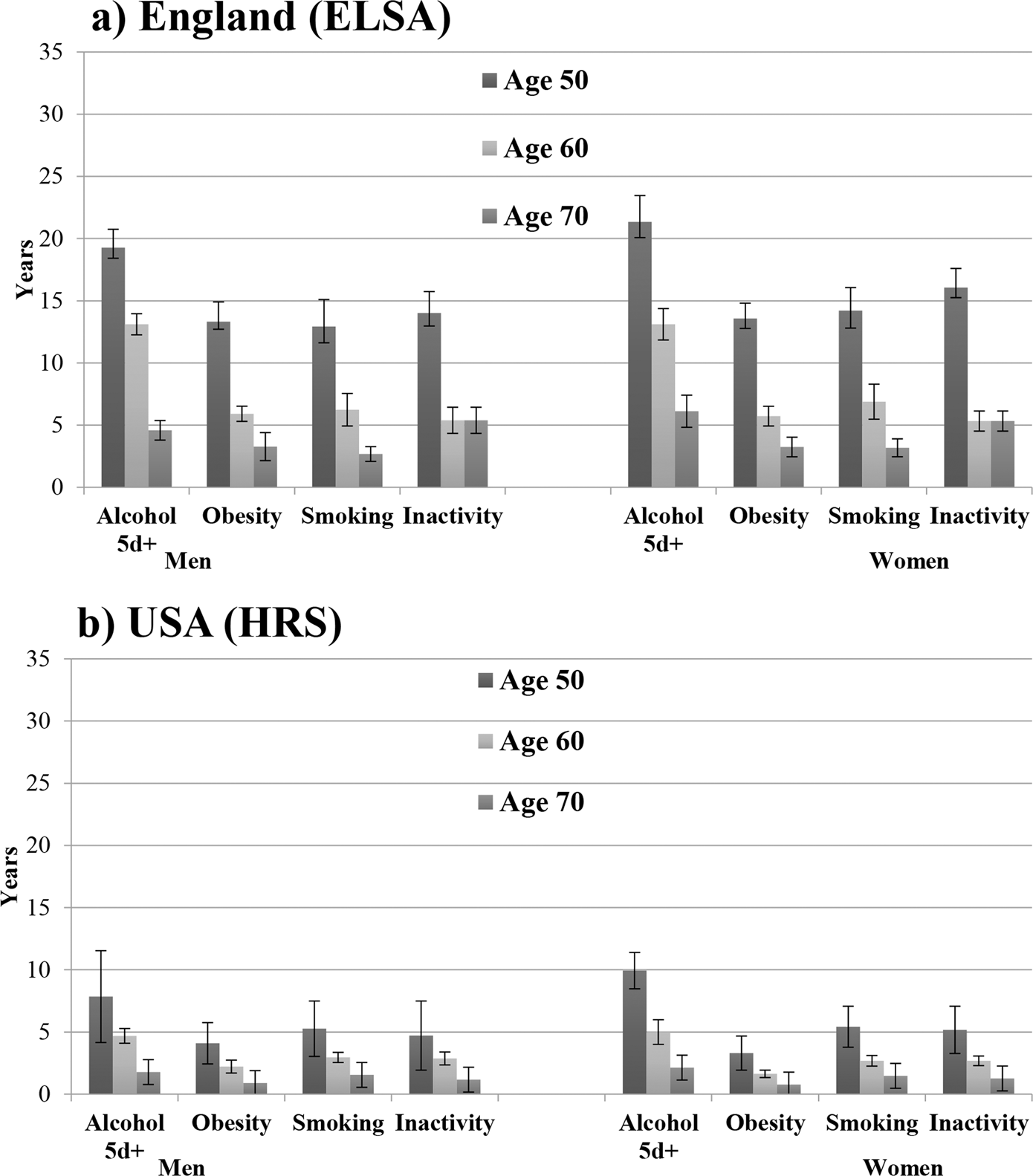

Paola Zaninotto, Jenny Head & Andrew Steptoe published an article regarding behavioral risk factors and healthy life expectancy: evidence from two longitudinal studies of aging in England and the US. [10]Zaninotto, P., Head, J. & Steptoe, A. Behavioural risk factors and healthy life expectancy: evidence from two longitudinal studies of aging in England and the US. Sci Rep 10, 6955 (2020). … Continue reading

They concluded that clustered behavioral risk factors are associated with shorter life expectancy, as well as, shorter healthy life expectancy.

Co-occurrence of the four behavioral risk factors are the following.

- Alcohol

- Smoking

- Physical inactivity

- Obesity

Estimates of total life expectancy according to the number of behavioral risk factors, by gender and cohort study England and Unites States 2002–2013.

| England (ELSA) | USA (HRS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years (95% CI) | Years (95% CI) | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Age 50 | ||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 36.4 (35.8; 37.8) | 40.1 (39.3; 41.4) | 35.1 (34.4; 36.2) | 38.9 (38.1; 39.5) |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 32.5 (32.1; 33.2) | 36.2 (35.6; 36.7) | 30.7 (30.0; 31.6) | 34.9 (34.4; 35.6) |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 28.4 (28.0; 29.3) | 32.5 (31.7; 33.1) | 27.0 (26.1; 28.3) | 31.8 (31.0; 32.5) |

| Age 60 | ||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 27.3 (26.4; 28.7) | 30.4 (29.6; 31.7) | 26.0 (25.4; 26.7) | 29.2 (28.6; 29.8) |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 23.1 (22.5; 23.7) | 26.9 (26.3; 27.4) | 22.5 (22.0; 23.1) | 25.5 (24.9; 25.9) |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 20.2 (19.9; 21.0) | 24.2 (23.6; 24.7) | 20.0 (19.5; 20.6) | 23.0 (22.4; 23.6) |

| Age 70 | ||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 17.9 (16.9; 19.0) | 21.2 (20.2; 22.4) | 17.7 (17.2; 18.2) | 20.1 (19.6; 20.8) |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 14.9 (14.3; 15.4) | 17.7 (17.2; 18.0) | 14.7 (14.3; 15.1) | 17.3 (16.9; 17.7) |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 12.9 (12.5; 13.3) | 16.1 (15.6; 16.5) | 13.6 (13.1; 14.1) | 16.0 (15.5; 16.5) |

Estimates from models with covariates age, sex, and wealth and interaction terms between age and behavioral risk factors.

The following table shows estimates of disability-free and chronic disease-free life expectancy according to the number of behavioral risk factors, by sex and cohort study England and United States 2002–2013.

| England (ELSA) | USA (HRS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years (95% CI) | Years (95% CI) | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Disability-free life expectancy | |||||

| Age 50 | |||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 33.3 (32.5; 34.4) | 35.7 (34.8; 36.8) | 31.7 (30.7; 32.7) | 33.5 (32.8; 34.2) | |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 28.8 (28.4; 29.4) | 30.5 (29.7; 31.1) | 26.6 (25.7; 27.7) | 29.1 (28.4; 29.7) | |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 23.4 (23.1; 24.4) | 25.2 (24.4; 25.7) | 21.1 (19.4; 22.8) | 23.7 (22.8; 24.6) | |

| Age 60 | |||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 24.4 (23.2; 25.7) | 26.0 (25.0; 26.9) | 22.6 (22.1; 23.3) | 24.0 (23.5; 24.7) | |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 19.6 (19.0; 20.1) | 21.8 (21.2; 22.3) | 18.8 (18.3; 19.3) | 19.5 (19.0; 19.9) | |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 15.9 (15.5; 16.6) | 17.8 (17.1; 18.3) | 15.3 (14.7; 15.8) | 15.3 (14.7; 15.8) | |

| Age 70 | |||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 14.9 (13.9; 16.0) | 17.0 (15.8; 18.0) | 14.7 (14.2; 15.1) | 15.1 (14.8; 15.9) | |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 11.7 (11.3; 12.2) | 12.7 (11.9; 12.9) | 11.2 (10.8; 11.6) | 11.9 (11.5; 12.4) | |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 9.2 (8.8; 9.7) | 10.3 (9.7; 11.0) | 9.5 (9.0; 10.0) | 9.4 (8.8; 9.9) | |

| Chronic disease-free life expectancy | |||||

| Age 50 | |||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 22.3 (20.5; 24.3) | 26.1 (23.7; 27.7) | 8.7 (6.7; 10.4) | 7.9 (5.9; 9.5) | |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 19.4 (18.3; 20.4) | 20.5 (18.5; 21.4) | 5.4 (3.2; 6.9) | 6.8 (4.7; 8.2) | |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 13.3 (11.8; 14.5) | 14.5 (12.8; 15.8) | 4.7 (3.3; 6.1) | 4.0 (2.7; 5.2) | |

| Age 60 | |||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 14.3 (12.7; 17.8) | 16.3 (14.4; 17.8) | 4.7 (4.0; 5.4) | 5.0 (4.1; 5.6) | |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 9.8 (8.6; 11.1) | 11.4 (10.5; 12.9) | 3.7 (3.2; 4.3) | 3.6 (3.1; 4.1) | |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 6.8 (5.7; 7.8) | 7.3 (6.5; 8.4) | 2.5 (2.0; 2.9) | 1.9 (1.6; 2.3) | |

| Age 70 | |||||

| No behavioral risk factors | 6.9 (5.5; 9.0) | 10.1 (7.9; 11.1) | 2.3 (1.8; 2.9) | 2.5 (1.9; 3.1) | |

| 1 behavioural risk factor | 4.4 (3.9; 5.4) | 4.4 (3.7; 4.9) | 1.6 (1.2; 1.9) | 1.7 (1.4; 2.1) | |

| 2+ behavioral risk factors | 3.3 (2.8; 4.0) | 4.0 (3.1; 4.7) | 1.0 (0.7; 1.4) | 0.8 (0.6; 1.2) | |

Estimates from models with covariates age, sex, and wealth and interaction terms between age and behavioral risk factors.

They found that, in both studies and at all ages, there was a clear gradient towards shorter disability-free life expectancy with increasing behavioural risk factors.

Chronic disease-free life expectancy at the ages of 50, 60 and 70 also decreased with increasing number of behavioral risk factors in both countries and genders.

Individual health behavioral risk factors and disability-free and chronic disease-free life expectancy for both men and women and each behavioral risk factor separately.

Disability-free life expectancy according to behavioral risk factors by sex, England and the United States 2002–2013 panel (a) England (ELSA) panel (b) USA (HRS).

In Figs. 1 and 2 we report the estimates of disability-free and chronic disease-free life expectancy, separately for each behavioural risk factors. Among men and women from England and the USA, smoking was associated with shortest estimated years of life free from disability at the ages of 50, 60 and 70 (Fig. 1).

The lowest number of years expected to live without chronic conditions, were observed among obese and physically inactive men and women from England (at all ages). In men and women from the USA, at the ages of 50 and 60, obesity was associated with the shortest estimated years of life without chronic conditions (Fig. 2).

Final note

There are a number of recurring, impactful healthy lifestyle changes that positively impact our health, such as

- Physical activity

- Healthy body weight (BMI)

- Healthy diet

- Not smoking

- Non-daily drinking or moderate alcohol drinking

Of course, these are not the only essential aspects.

Positive lifestyle changes such as getting an adequate amount of sleep, preventing substance abuse, and even simply maintaining a positive outlook on life will help one to live a longer, healthier, and more fulfilling life.

Call to action

A lot of us live busy lives. This makes it easy to get overwhelmed at times and thus, as a result, let certain healthy lifestyle changes we previously made slip into the background.

Yet, I advocate for people to start making slight, yet impactful changes in their lives. One small step at a time.

Popular and essential lifestyle examples include trying to get a little more sleep. (Who doesn’t like sleeping longer.) One could also start getting more physically active by going for short walks into nature a couple of times each week.

These small changes will add up over time and compound into great things. Just make sure to keep at it, even when the going gets tough.

Consistency is key!

References[+]

| ↑1 | Li, Yanping et al. “Impact of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on Life Expectancies in the US Population.” Circulation vol. 138,4 (2018): 345-355. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032047 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Farhud, Dariush D. “Impact of Lifestyle on Health.” Iranian Journal of Public Health vol. 44,11 (2015): 1442-4. |

| ↑3 | Grimaldo Muchotrigo, M. Calidad De Vida Y Estilo De Vida Saludable En Un Grupo De Estudiantes De Posgrado De La Ciudad De Lima. Pensamiento Psicológico, Vol. 8, n.º 15, Dec. 2010, https://revistas.javerianacali.edu.co/index.php/pensamientopsicologico/article/view/141. |

| ↑4 | Zhu, N., Yu, C., Guo, Y. et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Chinese adults: a 10-year prospective study of 0.5 million people. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16, 98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0860-z |

| ↑5 | Bergens, Oscar MSc; Veen, Jort MSc; Montiel-Rojas, Diego MSc; Edholm, Peter MSc; Kadi, Fawzi PhD; Nilsson, Andreas PhD∗ Impact of healthy diet and physical activity on metabolic health in men and women, Medicine: April 2020 – Volume 99 – Issue 16 – p e19584 doi: 10.1097/MD.000000000001958 |

| ↑6 | Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva L, Luksiene D, Virviciute D, et al Link between healthy lifestyle and psychological well-being in Lithuanian adults aged 45–72: a cross-sectional study BMJ Open 2017;7:e014240. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-01420 |

| ↑7 | Blom, E.E., Aadland, E., Skrove, G.K. et al. Health-related quality of life and physical activity level after a behavior change program at Norwegian healthy life centers: a 15-month follow-up. Qual Life Res 29, 3031–3041 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02554-x |

| ↑8 | Syed, I.U.B. Diet, physical activity, and emotional health: what works, what doesn’t, and why we need integrated solutions for total worker health. BMC Public Health 20, 152 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8288-6 |

| ↑9 | Janas Harrington, Ivan J. Perry, Jennifer Lutomski, Anthony P. Fitzgerald, Frances Shiely, Hannah McGee, Margaret M. Barry, Eric Van Lente, Karen Morgan, Emer Shelley, Living longer and feeling better: healthy lifestyle, self-rated health, obesity and depression in Ireland, European Journal of Public Health, Volume 20, Issue 1, February 2010, Pages 91–95, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp102 |

| ↑10 | Zaninotto, P., Head, J. & Steptoe, A. Behavioural risk factors and healthy life expectancy: evidence from two longitudinal studies of aging in England and the US. Sci Rep 10, 6955 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63843-6 |

1 thought on “Case study: The impact of a healthy lifestyle on our health”

Comments are closed.